Poor little rich girl

Edie Sedgwick, the cost of being a muse, and fame thirsty women haters like Andy Warhol

I hate the men who hate women for shining. The ones who want to suck with a straw a woman’s aura, and all her potential. Girls you know who I’m talking about. Maybe you’ve dated one, worked for one. Maybe you’re friends with one. Whatever you do, never let them imprint.

Beware of a man with a muse. I’m cynical because I spent seven years behind their lenses. They’re not all terrible, but it only takes one to kill you.

When it comes to women haters I will only give three examples because I mainly want to discuss the third while still throwing shade at the first two. I’ve ranked them from most to least promiscuous and I’m only talking about men (women are not exempt from being diabolical but I simply don’t have the time right now so I’ll leave it at this — if she tries to convince you to chop all your hair off, run). Moving on. Bad boys. H8rs!

Naturally, these types blend and blur — hate, like most things, exists on a spectrum.

He’s sexually omnivorous — sleeps (or “has slept”) with sex workers, racks up partners, probably juggles girlfriends and a wife while attending mass on Sundays. He judges women for any level of sexual activity, and when he hits rock bottom, he goes full brothel. Could be physically dangerous but not always. Either really ugly or wickedly handsome. Will weaponize your secrets, hobbies, and interests.

This one is trickier. He talks about women constantly — idolizes dream girls, hyper-fixates on celebrities, romanticizes the unattainable. Has sex, not often. Never commits. He thinks your body is his choice. He’s bitter and always slightly heartbroken that love never lands on him. Mala copa. Is good friends with #1.

The most dangerous of them all — jealous. This man hates women because he hates himself. His relationships with women are tense, possessive, and almost always asexual. Will also use your secrets and weak spots against you. He might be gay, might not be. The point is: he wants, desperately, to be you *cue Sam Rockwell’s recent WL monologue*.

He crowns one woman his muse at a time — and begins the quiet work of destroying her. He wants control of her beauty. Her confidence. Her brain.

He’ll call you darling, dear, or more modernly — babe. Tell you you’re a super star, so that you’ll work for free. He’ll be obsessed. Evil eye wrapped in compliments. But you’ll feel safe. Because he won’t try to sleep with you. And he doesn’t seem like he’ll hurt you.But he will.

He’ll do it in ways the others don’t. He’ll do it by shrinking you. Ignoring you. Gently, repeatedly, until you are small enough to manage.You know — bloodsucker, fame-fucker, Olivia Rodrigo’s words not mine.

I’m talking Max from Eve Babitz’s Sex and Rage.

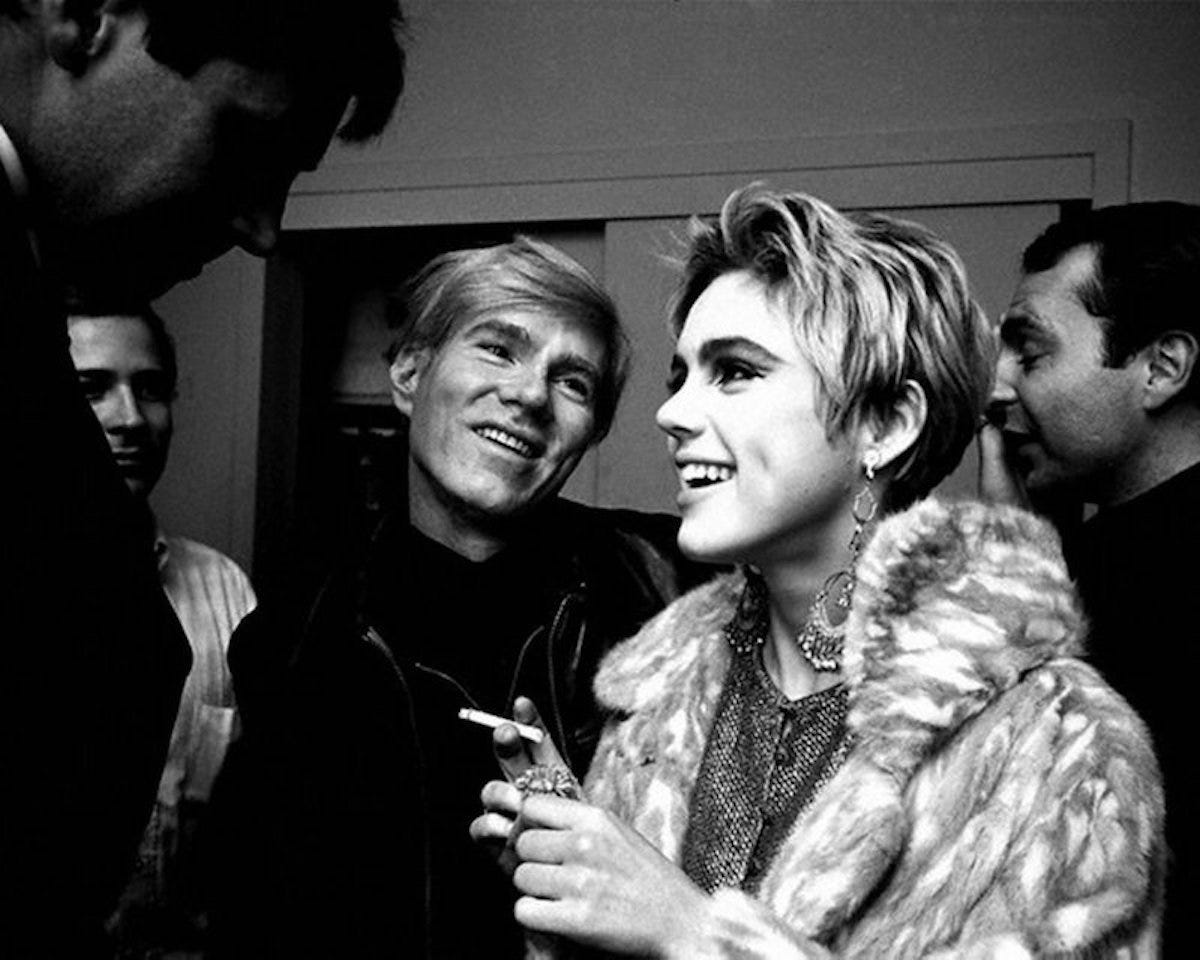

I’m talking Andy Warhol.I’m telling you that Andy Warhol killed Edie Sedgwick. Not physically so much as abstractly. He crushed her spirit and when someone crushes a woman’s spirit she either gets herself out of it or is as good as dead.

Edie wanted to be an artist. New York made her a model. Andy made her an actress — so he could direct her. Whatever role she played, it was always under him. But in truth, she stood beside him. To make him look better. It feels good to be adored.

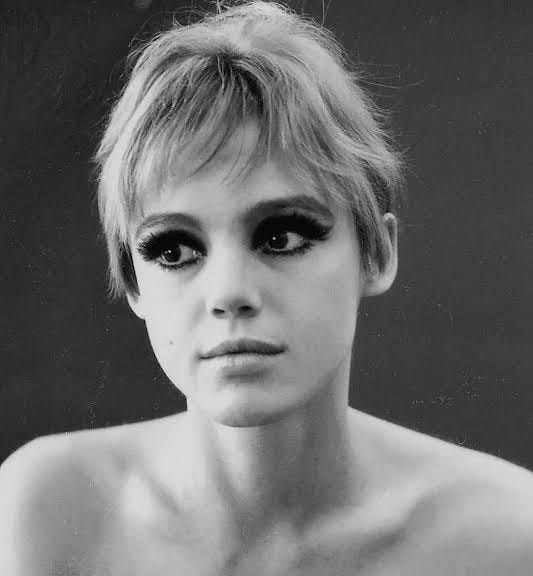

Edith Minturn Sedgwick Post was named after her great aunt, a Gilded Age socialite whose famous 1897 painting hangs at The Met. Born in California with old-money East Coast roots, she moved to New York after college and met Warhol, 15 years her senior, in the spring of 1965. As it often goes, the ones with the brightest light have already been to hell, and Warhol clocked this instantly. In The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, he recalled his first impression of her: “So beautiful, but so sick.”

When a woman is reduced to being the source of a man’s inspiration, something essential is stolen from her: the right to be seen as a creator, perhaps even the willingness to create. Her identity becomes secondary, flattened into his. Into his brand.

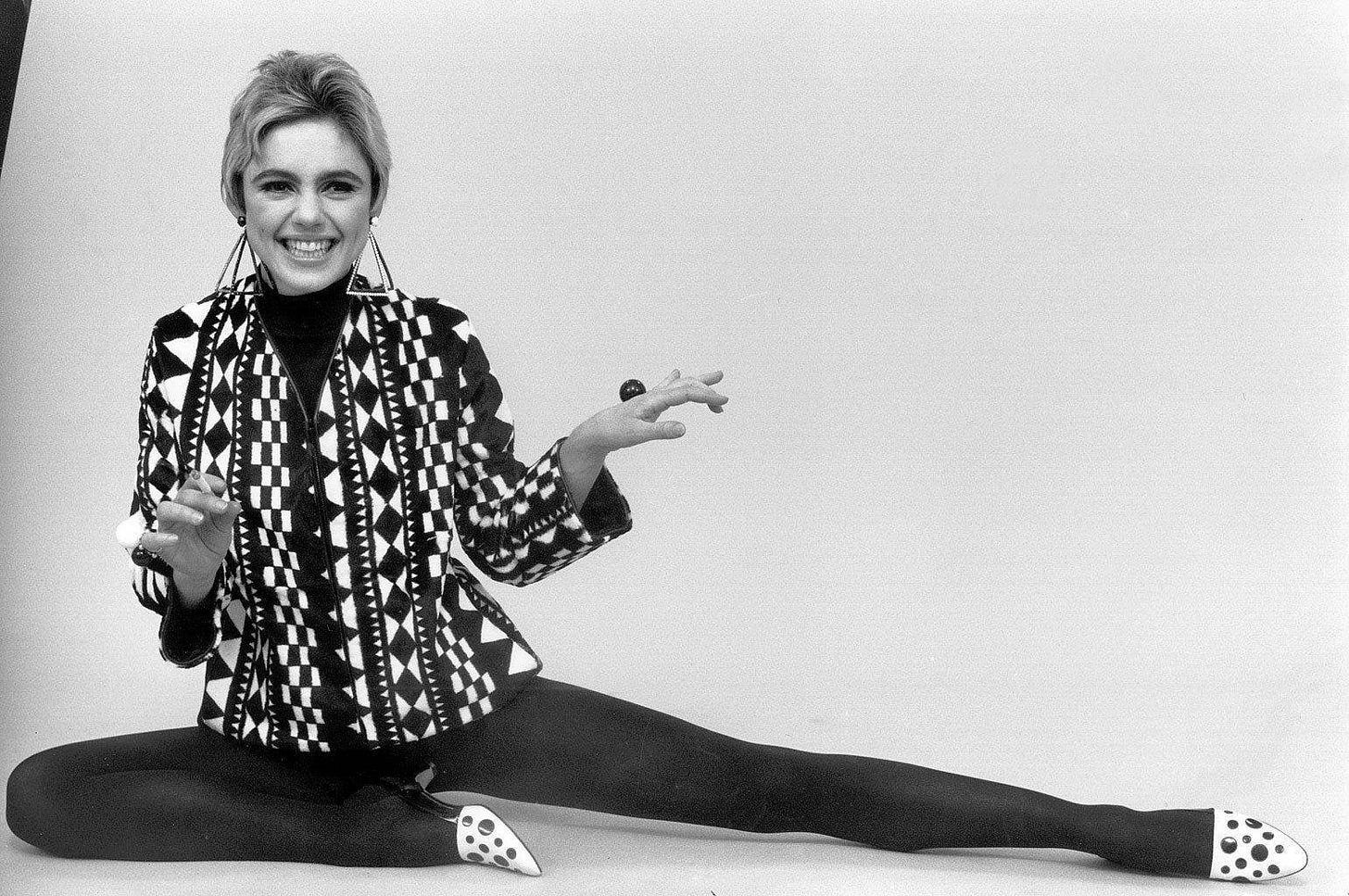

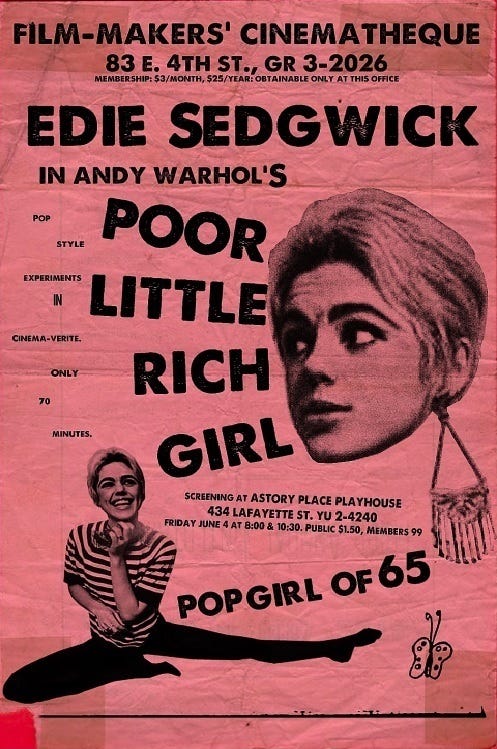

Edie Sedgwick is remembered not as the artist she once aspired to be, but as the tragic, glittering “Superstar” of someone else’s vision. After meeting Warhol, she seemed to shrink her own ambitions, playing the part he cast for her. New to the city, he sipped her dream right out of her heart and demoted her into his muse, featuring her in a dozen of his films, unscripted, plotless, often intoxicated. Their public stunt as power duo was intense and short lived — like the most toxic affairs usually are.

It was through the hazy lens of underground cinema that the mainstream began to notice her singular style: the black tights, chandelier earrings, iconic leopard coat. Being a fashion it girl, of course, didn’t threaten Warhol. He could handle her image. Her interior life was another story. It was in his best interest that she unravel.

At Warhol’s Factory, which opened just a year before Edie would first walk through the doors, New York’s misfits, muses, models, drag queens, drug dealers, heiresses, and downtown nobodies came to hang out, get high, and immortalize themselves through screen tests. The kind of scene Eve Babitz and Joan Didion captured in Eve’s Hollywood and Play it As it Lays. Babitz actually dedicated her novel to "Andy Warhol and Paul Morrissey who I'd do anything for if only they'd pay," alluding to the casual exploitation Warhol cultivated enabled by the decade’s drug culture. Babitz has been likened to Sedgwick, surviving the scene like Jacaranda Leven.

Edie finally fit in to a group of people as messed up and fabulous as she was. Only they were the wrong people, perfectly curated by Warhol to create an environment of mutual destruction, a world where beauty burned fast, and everyone was collateral. By the following year, Edie would be spiraling into heavy drug use, falling asleep with a lit cigarette.

But Edie's downfall wasn’t just cinematic — it was familial. Edie’s sister, Alice “Saucy” Sedgwick Wohl wrote a recent biography, As It Turns Out, featured in The New Yorker. She disputes parts of the more famous 1982 biography, Edie, and makes one thing clear: she didn’t particularly like her sister, admitting they didn’t speak for years and that “Edie wasn’t merely a victim of the big, bad art star.”

Wohl even dismisses some of the well-known allegations of sexual abuse against their father (a nasty man with a nasty nickname: Fuzzy), though she does note a psychiatrist once advised their parents not to have children. They went on to have eight.

So let's get things straight. Her sister hates her. Her father molested her. Within 18 months (and right before meeting Warhol) one brother commits suicide and the other dies in a questionable motorcycle accident. It seems Edie was wired to believe that those who loved her most, should hate her, should hurt her, and would leave her. No wonder she wanted to die.

When it makes sense that someone would want to die because maybe their dad abused them and their brothers just died and they were pumped with antipsychotics as a child it doesn’t really take that much to crush their spirit. You cannot recreate spirit.

Perhaps, by humiliating Edie, Warhol was attempting to absolve himself of the Catholic shame he could never seem to escape, by transferring it. But her freedom was never his to take, and he would spend his life chasing something he could never conjure. You see the thing about feelings, they can’t be faked. And the thing about shame is that no one can take it from you, not even the priest who instilled it.

Edie Sedgwick didn’t belong to Warhol.

He belonged to her. Like a parasite.

Edie’s magnetism was addictive and Warhol was starving. Warhol, an August Leo, behind the sunglasses and silver wigs was a man who always saw himself as awkward and ugly. Insecurity does not look good on Leos.

She was fearless, he was full of it. There’s a reason she was in front of the camera and him behind. She spoke for him, as if she was him. “Edie’s hair was dyed silver,” Warhol says in an interview, “and therefore I copied my hair because I wanted to look like Edie because I always wanted to look like a girl.” He used her like a shield, hoping that those who experienced Edie’s magic would only associate it with him. So people would look at him and feel her.

Seven months after meeting, Edie and Warhol appeared on the Merv Griffin Show. By October 1965 the two have now warped. Crash imminent. Warhol’s dedication to the act of being too cool to care may be hailed as art, but I see past the eye rolls and gum-smacking façade. She takes the seat closest to the host, Andy leaning away, mute. He goes on to give some one word answers, denies any emotional connection to his work, yet all the while seems terrified to be labeled, to be exposed. She’s the show, he’s the credit.

“What kind of emotion can you put into a Campell’s soup can?” Edie says, protecting him.

There is a scene in Factory Girl at a flea market where Warhol’s admiration gives way to irritation. He’s throwing lazy jabs about her wealth and ignoring her. When she calls Bob Dylan’s work meaningful, his ego evaporates. Silent treatment. Abuse abstract, like his art. Meaningless.

This isn’t about Bob Dylan (should I get into Bob Dylan?). Alright let’s get into Bob Dylan. Whether or not they were a thing, there was a something and it happened in 1965 shortly after she blew up as Warhol’s superstar. It is alleged that Bob Dylan's Just Like a Woman, Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat and Fourth Time Around from his 1966 album Blonde on Blonde are about Edie. Pretty sure he denies it. Hi Bobby you tell me.

At 23, Dylan was protesting with a harmonica. He wasn’t scared of pain, of being ugly. The type of artist Warhol wasn’t — real. A 1964 profile in The New Yorker recalls Pete Seeger remarking, "Dylan may well become the country’s most creative troubadour—if he doesn’t explode." Although Seeger was 45, he wasn’t much older than Warhol at the time. I wonder who Bob Dylan would have become without Seeger, and what Edie Sedgwick’s life might have looked like without Warhol.

In 1962, just three years before the three would somewhat intertwine, Edie Sedgwick was in a New England mental institution, Andy Warhol was printing his soup cans, and Bob Dylan was writing an unreleased song called Cuban Missile Crisis.

Anyway, according to her sister (the one who hates her), Sedgwick's life began to unravel after she cut ties with Warhol. She ended things by crashing out at dinner. She accused his films of humiliating her. She stormed off with Bob Dylan.

Rumor has it that one of Edie’s brothers claimed that she had been pregnant with Dylan’s child and then he married Sara. Ah sorry Bobby it’s just chisme. Either way, hurting a woman doesn’t make you a woman hater, leaving a woman doesn’t make you a woman hater, not saving a woman doesn’t make you a woman hater. What I’m trying to say is that Bob Dylan isn’t a woman hater. Not all men are and just because a man doesn’t choose you doesn’t necessarily make them a narcissist either. Bob Dylan is a super star, and super stars are usually lovers. I digress.

Edie’s survival would require sobriety, which she managed to briefly accomplish during her time at Cottage Hospital back home in Santa Barbara. But she wasn’t strong enough to truly face herself, let alone save herself. Within the year of her release from rehab, she married fellow patient Michael Brett Post, and relapsed shortly after, dying from barbiturate intoxication, an addiction that apparently began during her residency at the Chelsea Hotel, where she mourned her failed relationships with both Dylan and Warhol.

Following her death in 1971, Patti Smith wrote a poem titled “Edie Sedgwick” which was included in her 1972 poetry collection Seventh Heaven. The poem begins by highlighting that "Everyone knew she was the real heroine of (Bob Dylan’s) Blonde On Blonde" and continues:

I'll never dance

with her no never

she broke down

like a baby

she suffocated

like a baby

like a baby girl

like a lady

with ermine hair

oh it isn’t fair

and I'd like to see

her rise again

Ok let’s wrap it up. I take pleasure in how un-chic and un-cool the Andy Warhol Museum TikTok account is. A 2022 video begins with the trope: Did you know that Andy Warhol and Edie Sedgwick were a power couple in the 60s? The video has 1,240 likes and 20 comments, one of which reads, “power couple? he killed her.”

In response, the museum put out another video where a creepy older man denies it all, insisting that because she chose to be there, she couldn’t have been a victim.

Interestingly enough, the comment with the least likes is from an account called “Edie Sedgwick Community” whose bio reads: superfans is the oldest active FB forum dedicated to Edie & the community. I get it, no one wants to hear the ugly truth about a *power duo* when they’ve made a fantasy their entire personality.

But I guess thanks to the community, Edie’s legacy does surpass Warhol’s abuse after all. She was the fashion It Girl of the ‘60s. We love her. And she loved Andy. If only she could see his obsession was lethal. If only she knew the cost of being a muse.

She was an Aries, like me.

Today is my birthday, 29, the age she never lived to see.

I didn’t know Andy Warhol and Eddie, it was really a new thing for me and I’m still thinking about all that happened in her life. Also on my mind it stayed the “beware of a man with a muse” never thought about the cons of being a “muse” but made me think other way on Frida kahlo’s quote “I’m my own muse” only had taken it as, well she’s her own inspiration, but after reading this I see it more as a “I don’t let anyone to take me as their muse cause I have the power to have myself as my muse” like she had the power to tell her history and to create herself.

Thank you for this!

I had my own Andy Warhol, he was director of A&R at a record label and I was his intern.... his memory is slowly fading into the "many moons ago" category of my thoughts, but nonetheless when the ghost of him comes up, I still panic a little. -- tragic